|

In the last few weeks alone we’ve seen a lot of news from startups that have announced new technologies and services for collecting and analyzing wearables health data that promise to transform healthcare as we know it.

For instance, Siebel Health closed a $33 million funding round for scaling a wearables-based RPM platform; Prifina announced its new open source tools to generate artificial data for building health and wellness apps; and Vivalink published new blood pressure monitoring sensors. We’ve even seen nanotech tattoos that can detect your health problems. Those are just a few examples, but as a whole, they demonstrate how rapidly the market is developing. But will wearables change the healthcare sector just as fast? The rise of wearables tech Most wearables are not yet clinical-level devices, meaning they have no official status among health standards and regulatory bodies (for example, they haven’t received FDA approval in the US), so they cannot be used by health and wellness providers for healthcare purposes. Still, many people use these devices to monitor their own health and well-being. New-generation health and wellness devices also provide more insights into metrics and changes over time that that could be helpful for doctors. When I went to see a doctor a few months ago for a minor case, I told the doctor some of my Fitbit and Oura metrics, and he actually wrote them down in my health record. Meanwhile, there are many wearable manufacturers that are seeking official approval as health devices. I wrote earlier about CES 2022 and how, for example, Apple Watch, Withings, and Movano are working to get FDA approval. Of course, such approvals are long and slow processes and sometimes they make the development of devices slower. Technology is developing very rapidly, and companies must regularly bring new generations of products to the market, so they can’t always wait around for regulatory approval. I also wrote earlier that wearable data would be valuable for clinical trials. Wearable devices can offer much more data, help to find some rare symptoms, and decrease the costs of trials. Wearable data can help the healthcare system in many ways to make trials more effective, discover preventive methods, and understand public health better. Furthermore, they can also open many opportunities on an individual level and in daily health issues. Perspective on how rapidly things change The news announcements I mentioned at the start of this column were about services and platforms that enable more real-time monitoring and detection of unusual or more serious symptoms. We all know that it is not so simple and easy to develop applications in this area; health monitoring is quite a serious matter. At the same time, it would be important to find reasonable models to make it possible. We can say that it is always better to measure your health with approved medical devices and have a doctor analyze the results. Even so, we also know that it is not the reality; in fact, many people worldwide don’t have access to proper health care services. So, there are a lot of situations where technology can play an important role. I was just having a discussion about how, when I traveled as a young student in the early 1990s, we didn’t have the internet or mobile phones. The only way to get a message home was to go to a payphone and leave a message to an answering machine (which was literally a machine, with a cassette tape). Even 15 years ago, it was not yet really possible to navigate with your mobile phone – we still mainly used them for voice calls and text messages. Now we use our devices to track our friends in real-time on WhatsApp when they are traveling. We can make video calls with them at any time wherever they are. We can share pictures and videos of our trip in real time. We can book flight tickets, a hotel room for the next town, a driver to take us from the airport to the hotel, and a GPS-powered map to find our way around – all of this via our phone. This is totally ordinary now. Thinking about this reminds us how rapidly things change. Big change for healthcare is coming Looking at where we are now, we see early iterations of devices that can monitor our heart rate and other biometrics. More new devices with better sensors are being released at an accelerating pace. We can only imagine what this could mean in the next 15 or 30 years. And it is not only about sensors to measure things, but also the data from those devices that can be transferred in almost real-time to many places. Moreover, the processing power to combine and analyze the data is increasing. We know that wearables collect very sensitive data – much more sensitive than your location or your travel updates on social media. So, in that sense, the reliability of these devices is an important issue, as well as data privacy and personal control of that data. It is also important to be able to combine and use data from many devices. We don’t want to be in a situation where only a wearables manufacturer can make an app to monitor your wellbeing and health from its data. Now is the time when health care providers, insurance companies and regulators are recognizing the importance and significance of the fast-developing wearables and personal sensor market. There are already a lot of very interesting startups and tech companies building sensors, platforms, and ecosystems for people to collect, manage and utilize their personal health data. This will change healthcare significantly, although we don’t know for sure when – certainly over the next ten years, possibly as soon as three years in some areas. But while we don’t how fast that change will happen, we do know that clear rules for devices and data are needed. At the same time, it is also important to understand the opportunities these devices and services create for individuals, and the possible impact on public health. And we also need reasonable models to proceed. Thousands of companies buy and sell consumer data with other companies. Most recently, hundreds of business plans have been prepared, which essentially revolve around the idea of consumers selling their own data to monetize it. Probably neither of these models is a sustainable business. But what about consumers starting to pursue data from companies and public sources? Could it turn the perspective around? Does this sound strange? Let’s take a closer look at how such a proposition could make sense.

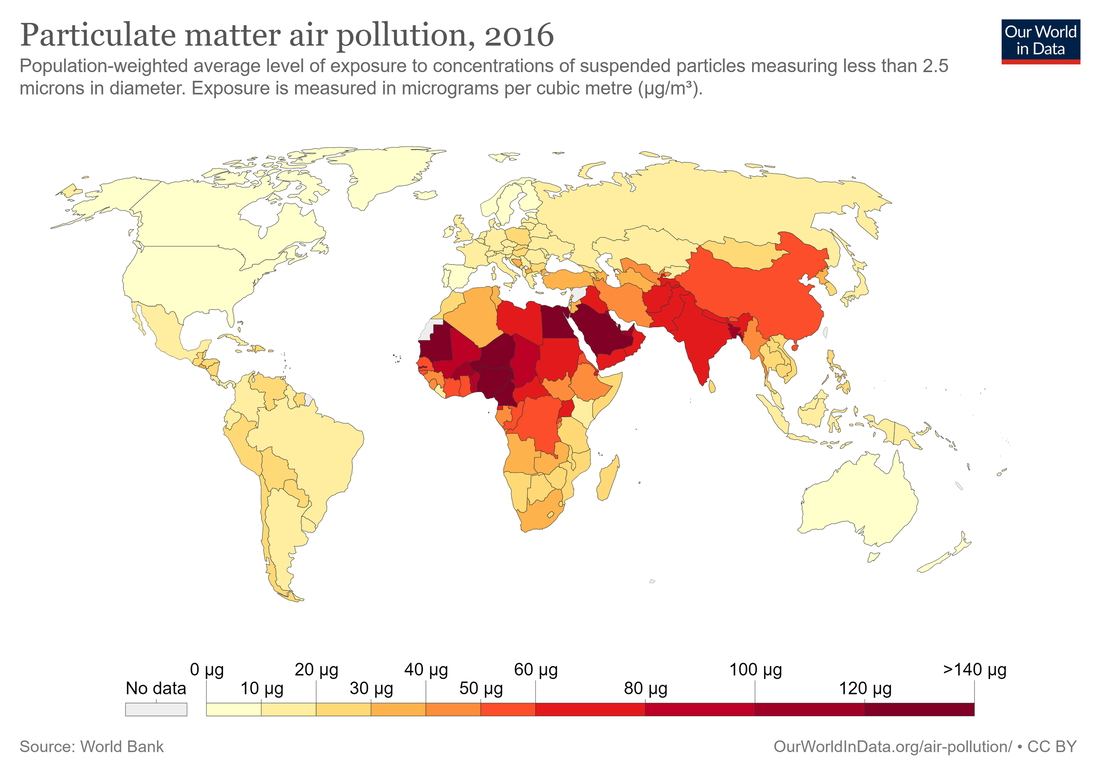

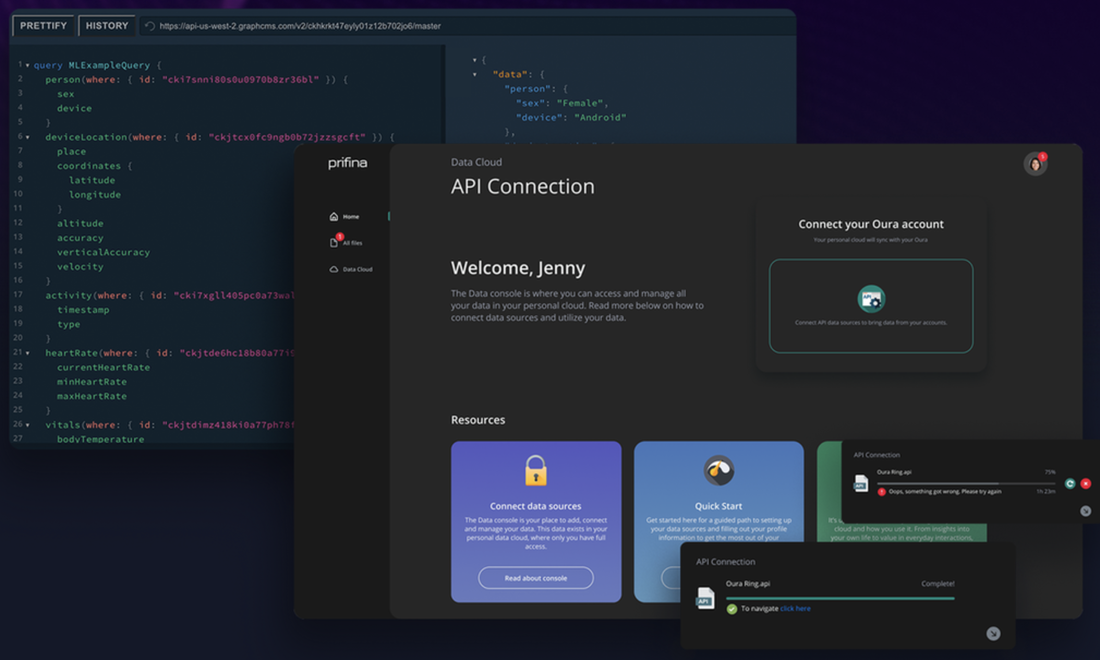

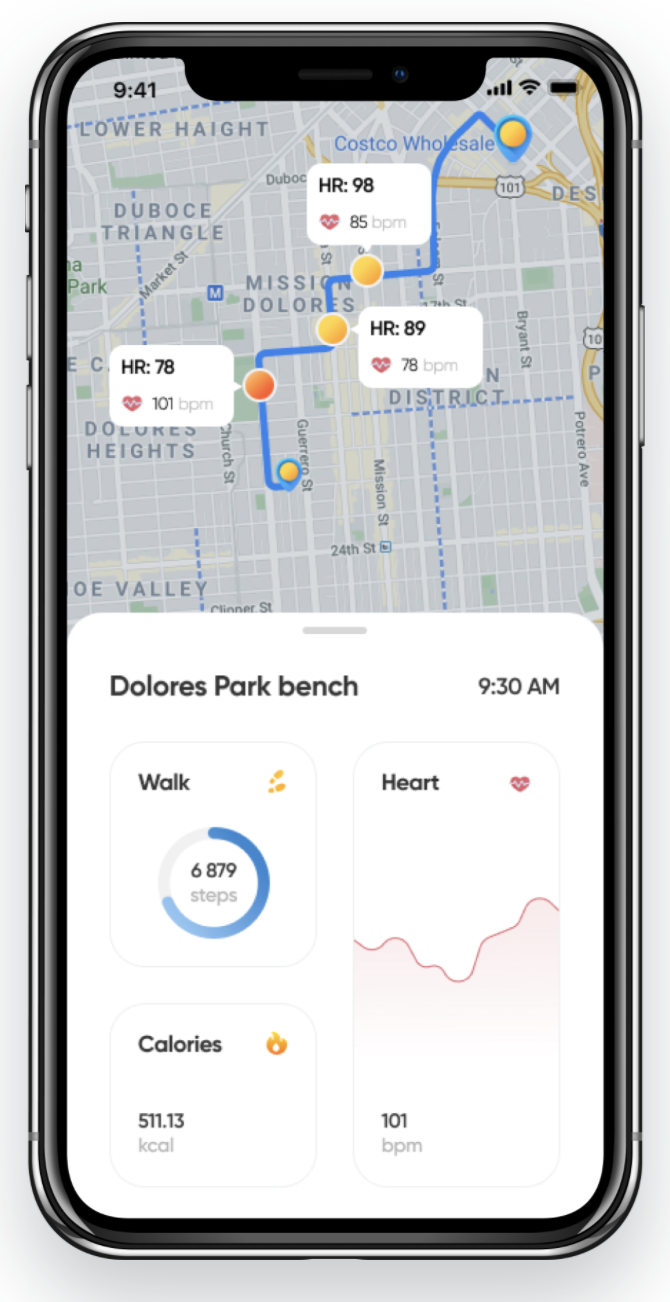

Companies collect and trade consumer data to make more money from consumers. Over the last few years, there have been several startups and business plans where consumers could gain a share of that money by selling their data. However, in reality, it is tough to get that kind of market to work. How do you define the right price? How do you control the use of the data? (Some people reply by referring to blockchain: perhaps, one day, but it is not that simple.) Are consumers keen to sell their data for a few dollars? How do you manage all different data sets, and to whom such data should be sold? There is no objective evidence that this type of market will happen or be of any value to consumers. Nevertheless, we see clear evidence that people can get value from their data. Their financial data could help with financial planning. Personal purchase history helps find the best places to buy. And health and wearable data can significantly help with individual well being, health and life habits. We can conclude by saying that the real value to consumers is that they can get value from their data or have smart applications to utilize it better. In some instances, personal data could also empower consumers against businesses using their data when it is not only one side that can use data and AI. More value from personal data with external dataWhen consumers can utilize their data, for example, for well being, optimal purchases, and finance apps, the natural next step is the possibility of combining external data sources with their data. A straightforward example could be when consumers could get better recommendations if they could combine their Netflix and YouTube watch history with some public data (such as IMDB). We already see apps that help consumers with their exercise, especially getting data from their wearables, analyzing them, and providing feedback to help people improve their activity. Further, what if we could combine some public data with personal wearables, such as air quality data? Then we can better analyze, e.g., heart rate and breathing, when we know if the air is highly polluted or contains a lot of allergens. It is then also possible to recommend healthier routes for exercising. Already today, we can start thinking about some commercial data that is offered to consumers. Today, you can already buy running routes from Strava. Then, we can make a much better application for runners. It can take into account the runner’s preferences, health data, air quality data, and good running routes, analyze all of this, and recommend the best and healthiest running routes. This is just a straightforward example. Still, it demonstrates that users can get value from their data and get even more value when public and commercial data are woven into unique data sets. We, of course, also have historical evidence that people buy data, e.g. stock and investing market data, when they want to become active investors. People now also pay to get DNA analysis, i.e. get their genetic data. We can also argue that news, maps, and books include data that people buy. However, in this post, we refer specifically to raw data that users can utilize with these personal apps. What data would you pay for? It is a kind of paradox that there have been many discussions about data markets where people are envisioned as selling their data to companies. However, a data market oriented in the other direction starts to look much more feasible. This is all linked to the fact that personal data and personal data apps can empower people and become even more powerful when combining external data sources with their data and apps. Let’s take a look at some other data sources that could make sense for consumers to use. For people planning a healthy diet, detailed data from food products could be of value. Ingredients, nutritional values and prices would help plan the diet, especially if combined with activity data, health data and, e.g. real-time glucose data. Would you be willing to pay $3 a month to get that kind of food data app that helps you plan your diet? Or would you pay a few dollars for more accurate traffic data that could be combined with your daily schedule to plan your days? Would you pay for a data source to get all grocery pricing data to optimize your weekly food basket price? Or would you pay for data that includes a lot of fitness training data that could, together with your exercise data, help to optimize your training? We are still in the early days with services that help you use personal data and have individual apps to get value from. But we can already see it is becoming a big thing. We also see how third party data, public data, and data from businesses can offer added value to personal data apps. And, somewhat surprisingly, we can also see personal data apps can provide opportunities for businesses to sell data to consumers. Then it is no longer that businesses intrude on consumers personal data and life, but offer people something that makes their life better and empower them. There is a ‘data rush’ on and it’s taking on the look and feel of the ‘wild west’. Nevertheless, a new order is coming.

In order to access, process, and share data, enterprises must comply with many regulations (such as GDPR in Europe, CCPA or HIPAA in the US) and sign many complex agreements such as DPA or BAA. Besides, companies increasingly depend on SaaS services that frequently need specific data related to processing the company’s data and sometimes bring some new data for the company. In this background, it is worth asking: Who can manage the multifaceted web of data flows? How many companies care about them? Yet, when something nasty happens, all relevant parties have to bear responsibility for their actions. Follow the data“Follow the money” is a famous quote from the 1976 movie, All the President’s Men. It was the hint to the Washington Post’s investigative journalists to find those who were responsible for the Watergate scandal. Similarly, when a data breach happens nowadays, we can say, “follow the data” to see who is liable in the end. And it can be expensive for the responsible companies, as it was expensive for President Nixon. Many companies are not sure what they are doing with all data regulations and agreements. Furthermore, they have a hard time evaluating the exact risk linked to these agreements and the data they use or share with third parties. The reality is that enterprises are more and more concerned about the liabilities that come with data. We can simplify and divide companies into two categories: 1) Companies that just sign all data agreements and add all needed regulatory statements but don’t evaluate what they do and what they should do with data, and 2) Companies that diligently evaluate all these agreements and regulations but still have difficulty understanding exact requirements. As a result, they end up paying a lot of money to lawyers and security experts. The first category of companies typically has comments from the executive team like, ‘don’t waste time with those stupid data rules; we need to do business.’ In a way, this is easy to understand. An enterprise might need to sign a few data agreements within a week when it uses some new tools or offers its own SaaS products. Executives are primarily concerned about data regulations that can freeze their business activities. At the same time, they then start to operate with rapidly growing risks. It probably means lousy luck that a company encounters a data breach. However, when dozens or hundreds of other companies use your services, and you use dozens of third-party tools, and all these parties again use the same network as other services, the risk can start to increase exponentially. In the first case, one company has a data breach, and many of its service providers and customers are also contaminated. It is fair to say it is impossible to get the risk to zero. You can decrease your risk significantly if you meticulously assess how to use other services, offer your product to other parties, and carefully evaluate which responsibilities you have. But this takes up a lot of your resources. Finding a way out of the regulatory jungleWe can conclude that data sharing, third-party tools and data regulations and agreements are a jungle nowadays. Regulators try to do their best to help consumers to protect their data privacy. Yet, sometimes they also make the jungle worse. At the same time, many companies don’t follow the rules, and we see a very wild data business. We can highlight several fundamental problems in the data business that are prevalent at the moment: 1) Companies can own individual’s data and trade it; 2) Many companies have very low competence and understanding of which data is beneficial to them and when it makes sense to buy or share data; and 3) Companies (especially marketing people and executives) over-estimate the value of big data and underestimate the intelligent use of that data. This also means that regulatory and legal activities to get current data models working correctly is tricky. Regulators must run behind these wild businesses and limit the worst problems when those companies don’t even know what they are doing with the data. We see startups that help enterprises better manage their data and privacy requirements and limit the exposure of data they have. There is a growing demand for these solutions. And it is easy to understand that this is a first step for companies to manage their risks better. We also see that the user-held data model is probably the long-term solution for consumer data. But it is a more significant step to take, and some companies need time to understand that it makes sense to all parties. We see now that these services are coming into use, especially in cases where a consumer can get real value from their data. Data business is the ‘wild west’ just now, and the sheriff can catch only the worst villains. Villains don’t respect other people’s assets or property. When the border expands to the west, everyone learns to appreciate the idea that each person has rights to their land and assets and that it is too expensive to mess with the rules. Now, some executives can afford to ignore rules for a time and hope to be lucky. Nevertheless, a new order is coming to data’s wild west, and sooner or later, each company will have to learn to respect individual’s data rights and personal data ownership. Blockchain and cryptocurrencies have been at the heart of discussions during the past five years. Some people have challenged the very core ideas about the existence of blockchain technologies and cryptos. In other instances, blockchain and cryptos have become a roller coaster ride. We have gone from hype to deep dips, and blockchain technologies have been considered both the catalyst for future technological advancement and a significant source of scams.

We know that timing means everything in business. So, it is worth asking if now is the time to introduce a blockchain-based business? Alternatively, what if it is not about timing but which specific applications and use-cases can make the breakthrough? Emerging communities of blockchain innovators I earlier visited Crypto Valley in Zug, Switzerland. Zug has been one of the places where special regulations for cryptos have been introduced. Consequently, Crypto Valley has built a technology and business community to accelerate blockchain and cryptocurrency businesses. The community and ecosystem include startups, accelerators, investors, advisors, and offers help from local authorities. My friend in the community said they have seen business activities growing this year. After the 2017 ICO hype, many parties in the blockchain business had hangovers. It has taken some years to get back to an actual business track. We can see the same situation in other places than Crypto Valley too. We can divide the challenges of blockchain business into three levels:

Moving beyond Proof-of-Concept Many larger companies have also developed Proofs-of-Concept (PoC) with blockchain. We have all heard about cases for supply chain, settlements and money transfers but are yet to see the momentum move from PoC’s to more significant scale production. There are several reasons for this, but at the same time, it is good to remember that enterprises like to try many things. They even have units to explore new avenues and squeeze startups to make them free with promises about future opportunities. But management often hesitates to adopt new solutions for larger-scale use. At the same time, many parties also make significant money with cryptos. They have become alternative investment instruments, and when prices have gone up, many parties have made good money with trading. Some of these ‘assets’ are also political, where investors like to see assets and instruments outside government control. Blockchain-based finance services constitute a distinct domain. They most probably will have a significant impact on the finance sector. But the timing is tough to predict when regulations, security requirements, and political issues (yes, governments want to control money) cause all kinds of delays and complexities. Nonetheless, if we think of blockchain technology as the basis of digital services, it is easier to predict the progress. The question is finding a stable enough platform, using suitable usability applications, and a sustainable business model. It is not easy to find these, but there are so many intelligent people working on these aspects globally that we will start seeing them soon. The real value is the crucial factor in finding the most valuable opportunity It is also advisable to ignore unrealistic services and business models. If your token is embedded in specific applications that people do not want to use, it has no value. If there is no way to use your sovereign digital identity, it has no value. If you have an NFT (non-fungible token) for an item that no one is interested in using or seeing, it is of no value. If you can create an app marketplace with many valuable and useful applications with NFTs, people will be more willing to use them and pay for NFTs. If you have a messaging service that offers real user value over other ways to communicate and uses a digital identity service, then the identity starts to have value. If a token is linked to a valuable service to confirm transactions, it has value. This sounds oversimplified, but it is so easy to forget these basic natural laws with new technologies. Now we can see applications, startups, and investors (Andreessen Horowitz is the best known) that we can expect real business built on blockchain. We don’t know yet which applications, when exactly, and in which sector the big breakthrough will happen, but we know for sure that it always requires a lucky coincidence of many factors. Yet, when there are enough activities, enough smart people and enough money, it will happen sooner than later. Maybe then the roller coaster will stop. API-first architecture is an approach to software design that is centered on the API to make it easy for applications and services to interface with each other. If we really simplify, it is like having a ‘socket’ in the service that other services can work with. API-first is also a business approach, enabling developers to build applications on other services and enable others to use your services in their applications. API-first has been a popular approach in designing services for a few years now; however, in many services it is not a reality. It is a strong concept for building successful future services and applications.

Economic significance of API: theory and practice A research paper published several years ago demonstrated that APIs have a real impact on companies’ business success. The paper concluded “that firms adopting APIs see increases in sales, net income, market capitalization, and intangible assets. API use also predicts decreases in operating costs in some specifications. The extent to which API adoption is linked to this outcome is sensitive to the econometric specification.” The authors of that paper also found that API adoption was strongly related to increases in net income and operating income and that the most significant relationships turn out to be between API adoption and market value. It is not enough merely to have API’s; instead, what matters most is the ability to properly design those APIs so they can actually support integration to other services. For example, Slack’s API design guidelines give very practical instructions on how to make good APIs. They also illustrate that the devil is often in the detail. Hence, you must think carefully about which services you would like to offer over APIs, how you offer them, and even how you support error issues. We have quite a lot of help and guidance on how to make the API-first approach work but it doesn’t mean that many companies have actually adopted the API-first approach. Even if they have taken it, their APIs are not that useful in reality. Then we have regulated interfaces, such as the 2015 EU Directive on Payments and Services (“PSD2”) in banking and electronic health records in the European Union. Yet many of these are quite limited and difficult to use. Business opportunities with the API-First approachSurprisingly, many companies are still of the opinion that an API is a risk or a mandatory component. Few companies really seem to look at it as a business opportunity. For example, if they open an access point to their data, they think that other parties could make something better with the data than they can. And vice versa, some companies hesitate to build services on other companies’ API’s and prefer to manage the whole stack themselves. Let’s look at a couple of examples. Several years ago, we founded an API-first finance back office as a service company, Difitek. In many ways it offers a really attractive model to build financial services. Its cloud based back office offers many functions such as banking IT and beyond. It offers functions to manage KYC, loans, investments, account management and many other finance functions. However, we have seen that for traditional finance service providers it is difficult to use external services, even though they see cost benefits, see how it can accelerate new service development and improve customer experience. Many new fintech companies want to build their own stack, not build on external API’s, especially when they think it is important to own intellectual property rights to their technology. Another example is wearables and their data. Some wearable devices offer quite nice APIs to collect data and then utilize the data elsewhere. But many of them don’t yet offer an API, or the APIs are hard to use in practice. Most stakeholders in the wearables industry agree that it would be advantageous to combine data from different sources and to have a more open market to develop apps on data. Furthermore, the use of wearable devices would increase if the APIs to utilize wearable data were more open. Paths towards opening the API ecosystemAs a whole, it looks as if many players see the value of API’s. However, most of these market players don’t want to be the first mover. They believe they don’t want to open anything until other parties do so. At the same time, business history has shown us time and again that it is generally not a smart strategy to try to delay an obvious change and act only when it is absolutely mandatory. We have, of course, many good examples of where the API-first model already works. Stripe is one of the most valuable fintech companies and it is very much an API company. Twilio is another good example. We could also mention companies such as Shopify, Okta, and Square. We can clearly see the API-first model as a good business itself. Public sector companies with open data has also demonstrated the value of APIs. The API-first model offers significant business opportunities. Nevertheless, businesses need more courage to actually adopt the model. Many companies believe that it is safer to offer their own services and at least limit the openness and APIs to a minimum. It also requires companies to really know their own business model and to disrupt the market with it. The future belongs to those who really are able to offer and use APIs and build their business on it. Delaying an inevitable change is never a good idea. Smartwatches are making an impact on the watch market. Watch enthusiasts favour traditional watch brands, ‘mature’ buyers and those who need to show off their wealth. Younger generations tend to go for smartwatches. Smartphone brands have been highly successful in the smartwatch market, but traditional watch brands haven’t been successful in the mobile phone business. Even Vertu that targeted a luxury brand position, failed.

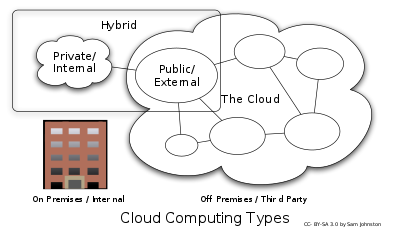

We also don’t see jewellery companies coming to challenge Öura in the ‘smart ring’ business. So, why is it so difficult for luxury brands to be successful in the tech business? Could some changes in the tech service market change that situation? Why are smartwatches mainly coming from Apple, Samsung and wearable tech companies like Fitbit, Garmin and Withings, rather than the traditional watch brands? Is it linked to the technical development and disruptions in the market that state-of-the-art technology inside devices is more important than brand status? Or is it that digital products makers find it more challenging to become status symbols because their customers go after price, usability and usage value? An access device is a tool with little intrinsic value in itself. With digital products, the value is really in the Internet, cloud and associated services, not the device itself. The device must offer almost invisible access to the service. That is why Apple’s most significant value has been a seamless user experience; why Amazon offers its tablets for a very low price, and why Google tries to manage software on all devices. People also look for different kinds of experiences with luxury products than daily tools. One learning is that luxury products are typically designed for a particular need, not packed with multi-function technology. Luxury products like expensive watches, coffee machines, pens and supercars generally are for specific situations and do not compete with products for regular everyday use. But very specific functionality is not enough if people start to expect basic smart functions for all devices. For example, people expect to get their exercise (e.g. steps), heart rate and sleep data from every watch. This means those functions are no longer something extra but the basic functionality they expect to get from any watch they buy. Any watchmaker could quite easily add sensors to measure movement, heart rate and sleep. Those sensors are becoming a commodity. The complex part is to build the complete service and infrastructure for it. The data must be collected from the watch and stored, and the data must be organized, analyzed, and presented to the user. The user needs an application to access, utilize and analyze the data. Brand companies need to invest heavily in infrastructure, software development and data analytics to compete. It is not a one-time investment but one that would require continuous maintenance and development of the services. Now, these devices and their data live mainly in their silos. Apple Watch, Samsung Watch, Fitbit, Withings, Oura, Garmin and many other devices have their data formats, data storage, services and apps to use them. It is a device-specific vertical market, and you need all components from the same manufacturer. But maybe there could be an alternative? Suppose data from various devices go into the user’s one data storage. In that case, it can combine data and have an open API to develop applications, making the whole wearable market very different. It also makes the role of brands very different. When we get more horizontal layers for the wearable market, it will be easier for other brands to come to the smart wearable market. Suppose you are a Swiss watchmaker or a Milan-based fashion brand. In that case, you can easily add sensors to your watch, shoes or clothes, with data collected to the user’s database, and there are many applications to utilize the data. This is a much smaller and easier investment for brands rather than building the whole infrastructure. People could then buy or use several different branded products, and the same data and application model would work for all. There would be an army of developers making apps on the API and updating them when new devices, versions and clothing come to the market. This model would be of value for houses of brands that cannot compete in the wearable data and app business market. For obvious reasons, tech giants like Apple and Google won’t particularly like this development. It is also a risk for brands to rely on Apple’s or Google’s services and become dependent on them. I wrote earlier that the wearable market is like the 1980’s computer market or 1990’s mobile phone market. Then the software started to dominate the market. When software and data analytics capabilities begin to dominate the wearable market, it will change the market significantly. There might be a few software vendors and data infrastructures that come to dominate the whole market. Or it could be a more open user data-driven infrastructure that is open to all devices and application developers. We already know that most cannot create their complete infrastructure and choose between tech giant’s walled systems and user-centric models. Brands must also make a realistic evaluation of which model they want to support to survive and succeed. When we talk about Silicon Valley and California, we often make references to the California Gold Rush. How many times have we heard that only a few gold miners made good money? But the same gold rush spurned companies like Levi Strauss, Wells Fargo and Ghirardelli Chocolate that started to offer products and services to gold miners. Today’s comparison is not the abundance of developers out there but the companies developing tools for them that are the big success stories. What could be the next area offering successful ‘tools’ to find gold?

Think companies like Github, AWS, Snowflake, Stripe, Databricks, Plaid or Segment. They are not so well known among consumers, but they are all big tech unicorn success stories. All of them are tools for people software development, data pipelining or build IT services. They are tools for professionals, not consumers. From an investor’s point of view, it’s a no brainer to invest in a shovel store near gold miners or building sites, in preference to an individual miner who tries to find gold amongst thousands of others. It is a much more predictable business, and the risk is better diversified. Software development, cloud services, data pipeline and open-source tools have been a hot area in tech investments for at least 20 years. With software going to the cloud, and there are now tools to better collaborate and share components in software development, get enterprise data from one system to another one and integrate external services. This has made software development, data utilization and software distribution much more effective. Software developers and data scientists are the gold miners of our time. But it is never that easy to build success stories for the future based on the past. It should be evident that when miners can’t find significant new gold in an area, it is no longer a good business to sell shovels, jeans or banking services there, either. You must find a new location where those tools are needed and help those miners improve their business or make new products that allow them to do something else. You must operate in areas where enough miners or developers are seeking their fortune, and enough of them believe they can make money with your tools. Where are we now? Can we see some new areas where developer tools are needed, where developers are starting to find gold? We can see some areas are quite crowded, and there are already lots of shovel stores. For example, enterprise data solutions, enterprise IT integration tools, game engines, or low-code tools are all growth areas. It doesn’t mean that one can’t make money there, but the competition is fierce. Nevertheless, some lazy investors are still ready to bet on those areas. So, what could be the new areas needing new tools? Even if you knew, you probably wouldn’t want to make the information public. But it does make sense to evaluate the underrated areas. Today, it seems that sharing information and collaborating is a better way than operating alone and in secrecy. So, let’s try to evaluate some areas where it could make sense to go and sell shovels: 1. Distributed solutions – including blockchain, distributed ledgers, edge computing, distributed data models and decentralized marketplaces. 2. Personal data – the focus on data tools and pipeline solutions has been on enterprise data, but when individuals produce, collect and utilize personal data, a vast market will emerge that will need tools to utilize it. 3. Automation with AI – AI is quite a crowded market, but its tools focus on data modelling, not on building end-to-end solutions, i.e. having AI brains and hands. 4. User-friendly security – data security, trusted communications, privacy and system security often mean restrictions, an unpleasant user experience and limited services. A real breakthrough would be tools to develop new services with better security, control, and user experience. These are some examples of potential areas to find significant new gold and build developer tool companies that become unicorns. Of course, the most visionary and risk-taking investors have already become active in these areas. And, as always, some tools will work better than others, and not all miners will find gold. The complex phase is introducing a new tool to the market as it can be challenging to get the first buyers, or if people have previously used another tool for the same purpose. However, if your tool is better, you need examples that some miners are finding more gold with your tool. That’s why in the early days with a new tool, you must cooperate with some miners to generate success with your tool, and you must be able to demonstrate that you can find more gold with your tool. If you put all your money into building a big store that can serve hundreds of customers and wait for people to turn up, you might run out of money. You can always expand your store after customers start flowing in after hearing stories of how people have made money with your tools. In the tech business, it seems to be just like 1849, Groundhog Year. Developers or miners are looking for new precious metals in new areas, and many startups try to offer them new and better tools to make their work more effective. In the end, the money comes from those who buy and use tools, applications and services. Developer tools are a great business, but it is not a sustainable business if developers can’t find the gold with them. Apple opened its App Store in 2008. It was the start of a totally new type of business. Now we can run apps on iOS, Android, TV sticks, computers (earlier, they were just programs). Many other service providers like Zoom, Stripe, Weebly, Snowflake and AWS also make it possible to build and offer apps and services on their platforms. It appears that enabling apps on a platform is a popular way to scale up businesses.

What could we see next? The big players monopolize the current app marketplace, but this ‘old model’ has its challenges for new players. The future disruptive marketplaces will be more decentralized and have new data models. Apple’s App Store has played a vital role in getting the iPhone to be the most successful mobile phone, but the apps themselves are a significant business to Apple. The App Store has been an enormous success and has become Apple’s most profitable business. Even though Android is the most extensive mobile operating system, its applications haven’t seen similar success. There are many reasons for this. Apple controls its ecosystem, but the Android market has been more fragmented, with fewer controls allowing lower quality apps. As a result, Apple’s environment generally offers a better user experience. South Korea is aiming to end Apple and Google’s commission dominance. Apple has been able to take a massive 30% fee from sales on its platform. Epic Games has challenged that position in the last year by bypassing App Store payments in its games and suing Apple for its monopoly position in the App Store. Now, a group of Senators in the US is also considering how to restrict Apple’s and Google’s control on the app market. Apple is already making App Store concessions to settle the developer suit. We will see how this ends. No other platform has achieved a similar position to the App Store. However, this hasn’t stopped multiple parties from expanding their platforms to third-party applications and targeting lower margins from the sales of apps. Sometimes the target is really to make additional revenue, but often it is just to get more popular applications on the platform and, in that way, get more use and users. The value of application stores and marketplaces for users is primarily in accessing good quality applications in one place; buy, pay and install them easily. That’s why they have become very centralized services, basically one place to purchase and pay for all applications. App Store or Stripe payment solutions have been the most straightforward solutions for consumers to pay. All this has been very centralized, technically, also from the business model point of view. Now we see a move to more decentralized solutions utilizing blockchain, whose journey has been bumpy. It also means there are new ways, like NFT, to make payments, create economic models and monetize applications. Andreessen Horowitz has been the most active Tier 1 VC to invest in distributed models, and their a16z podcast discusses how nowadays a marketplace makes sense to build on distributed architecture. Then we have another important megatrend, privacy, and how users can better control and utilize their own data. This creates another challenge for centralized application business models. Many of these applications want to collect user’s data and share that data with other parties or utilize it to target users. Users have become more skeptical of this model, and Apple has also started to restrict it. These things together lead to a new era in the application business and marketplaces:

The change from the old centralized application business to a more distributed model won’t happen overnight, and it takes time. It is hard to envisage emerging new big platforms using the old model, like Apple’s App Store. The centralized application marketplace business is a copycat business nowadays. The disruptive application marketplaces will come with new models. In the future, you can keep your financial and health data to yourself and run applications to analyze it and get practical advice for your life. You can run it in your mobile or personal cloud and pay with a commonly used token (e.g. on Ethereum) for each time you use it. There is no need to give your data to someone, no need to pay a fixed fee for the application, and no third-party monopoly to dominate the marketplace. Sounds ideal. Of course, each model has its challenges, but we have a real opportunity to move to a more user-centric application business. The next big success stories in the consumer market will be achieved with these new marketplace models. The co-founder of Google Brains, Andrew Ng, commented that “massive data sets aren’t essential for AI innovation.” Some years ago, I spoke with a person from a tech giant that also wanted to get into the data business. I asked him what data they wanted to collect and how it would be used. His answer was to get all possible data and then find a way to utilize it. His response says a lot about the data business.

Many companies want to start their data journey with a massive IT project to collect and store lots of data. Then the discussion is easily about IT architecture, tool selection and how to build all integrations. These projects take up large amounts of time and resources. What is rarely considered is the real value we want from the data. And even if we have a plan for that, it can be forgotten during months or years of IT architecture, integration and piping projects. These projects are not run by people who want to utilize data; they are often run by IT bureaucrats. Mr Ng also commented that people often believe you need massive data to develop machine learning or AI. There seems to be a belief that quantity can compensate for quality in data analytics and AI. I remember having a discussion with a wearable device company when their spokesperson claimed you needed data from millions of people to find anything useful for building models. There are use cases where big data is valuable. Still, the reality is that in many use cases, you can extract considerable value from small data sets, especially if the data is relevant. We can also think of horizontal and vertical data sets, e.g. do we want to analyze one data point from millions of people or numerous data points from a small number of people. With the horizontal and vertical data, I don’t mean how they are organized in a table, but the horizontal approach to collect something from many objects, e.g. heart rate from millions of people, versus the vertical approach of having more data from fewer objects, e.g. a lot of wellness data from a smaller sample group. But does it help to understand an individual’s wellness, sleep and health better? Looking at wellness data as an example illustrates the question well (no pun intended). A wearable device collects steps, heart rate and sleeping time from millions of people. We can then analyze this data to determine if more steps and a higher heart rate during the day predicts the person sleeps longer that night. Then we can find a model that predicts similar outcomes for other people. We can take another model to build analytical models. One individual uses more wearable devices, for example, to collect the usual exercise, heart, and sleep data, but also blood pressure, blood glucose, body temperature, weight and some disease data. Now we might get different results about heart rate, step and sleep relationship. We might see that their relationship depends on other variables, e.g. high blood glucose or blood pressure changes the pattern that works for healthy people. These findings can be determined from a small number of people. The examples above are not intended to make any conclusions about what is relevant to analyze health. Those conclusions must be drawn from the data itself, but it illustrates how it is possible to take different approaches and get quite different results. Wearable data at the moment is a good example of big data thinking; the target has been to collect a few data points from millions and millions of people and then just train data models to conclude something from it, although we don’t know how relevant those data points are. It is also possible to build models from rich data of a few individuals, and actually, it can be an exciting and valuable AI modelling task. Of course, there are also cases where data models can be built from a massive amount of data even though we don’t know if it is relevant. For example, this podcast talks about hedge funds that try to collect all kinds of data and then build models to see if they can predict stock market movements. This includes much more than traditional finance data for investments. For example, how people buy different kinds of food, watch streaming content, and spend their free time and then find ‘weak signals’ to predict trends and their impact on the investment market. So, compared to many other data analytics cases, it is different because it doesn’t focus on analyzing particular detail but randomly collecting all kinds of data to see if it can find something relevant from it, hoping to find any new variables that could give a competitive advantage. In most use cases, utilizing data and building AI would be important in understanding the need and target. Relevant data can be then chosen based on actual needs and testing which data matters. Small but relevant data can produce a useful AI model. This typically requires the context to be taken into account, not only a lot of random data points collected with a model built. Whatever data you have, you can always build a model, but it doesn’t guarantee the model makes any sense. Companies and developers should focus more on relevant data than big data. Enterprises have been moving their services to the cloud for several years. Peer-to-peer (P2P) services have become well-known, especially with blockchain and crypto. But individual users haven’t really used personal clouds, and the number of real P2P services is still quite limited. But this could soon change.

I wrote earlier about decentralized solutions. Personal clouds and P2P apps are examples of distributed applications mentioned in that article. But let’s take a more concrete and pragmatic approach, what these applications could be and how they work. I was recently demonstrated some services that are basically apps that users can run locally in their own browser and have data either stored locally or in the user’s own cloud.

These examples might sound simple, but they could be the start of a big revolution in applications and even how the internet is used. Of course, the very fundamental protocol of the Internet, TCP/IP, is based on packets routed from A to B. But in practice, most services during the last three decades have been based on client-server configurations, not local services and/or direct connections between users. These services raise several technical questions about whether usability would be good enough for mainstream users. For example, users can already set up a connection by sending an invitation with a traditional email and then making the P2P connection with local credentials and sending messages directly or through centralized services like email or messaging apps. An interesting combination occurs when services use the user’s local applications and the user’s own cloud or similar storage services. It is hard to store and organize all of a user’s data locally when using several devices. However, the scenario changes if users have their own storage services and can get the needed data and apps from there for local use when needed. This storage is not a third-party central service but the user’s own service in a broader global infrastructure. It sounds complicated, but does this really matter? With blockchain and crypto, we have seen how users can make transactions directly without third parties. It has enabled reliable payments anonymously without an authority or central service to track all transactions. It can offer a more reliable system, better privacy and no single point of failure. But with these user services and P2P connections, we can do much more than simple crypto payments. Let’s take some examples:

Blockchain and tokens have received a lot of attention, but the examples above better demonstrate distributed applications and peer-to-peer communication. Blockchain and tokens can also be a part of these services. Blockchain could provide a ledger to keep track of transactions and tokens as a model to monetize distributed services. But they are not services alone. It is fundamental to have applications and services that are valuable to users, and then we can use blockchain and tokens in the implementation. The question is, which services will provide the real breakthrough of user’s personal clouds, apps and pure P2P services, and when? They will probably be linked to personal data, self-sovereign identities, trusted communications and data sharing. We just need a few easy to use applications and after that things can start to evolve rapidly. The article first appeared on Disruptive.Asia. |

AboutEst. 2009 Grow VC Group is building truly global digital businesses. The focus is especially on digitization, data and fintech services. We have very hands-on approach to build businesses and we always want to make them global, scale-up and have the real entrepreneurial spirit. Download

Research Report 1/2018: Distributed Technologies - Changing Finance and the Internet Research Report 1/2017: Machines, Asia And Fintech: Rise of Globalization and Protectionism as a Consequence Fintech Hybrid Finance Whitepaper Fintech And Digital Finance Insight & Vision Whitepaper Learn More About Our Companies: Archives

January 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed